I posted a few days ago about a trip that I took down to the Polaris Sci-Fi Convention in Toronto. Since I have a full 45 minute talk all laid out I figured I would give a little bit more detail about the topic.

[tl;dr: superstitions are the brain’s rational way of dealing with incomplete information. They form readily and are not unique to humans. While we cannot always be right, there are ways to reduce the number of times and number of ways in which you are wrong. Think scientifically, not anecdotally, search for scientific research and beware logical fallacies!]

My talk was in five sections:

1. Superstition in people

I gave a number of examples (fish in a barrel stuff, really…) of superstitions that people believe in. Examples included (i) Laurent Blanc, the French soccer captain, kissing the bald head of Fabien Barthez, the French goalkeeper, prior to each game in the 1998 Soccer World Cup, (ii) the fact that a lot of aeroplanes are missing rows which correspond to “unlucky” numbers (see the image of the All Nippon Airways jet which is missing several), (iii) power bands as 21st century rabbits’ feet, and (iv) faith healers. I made the point that these were expensive (power bands) or dangerous (faith healers, when used instead of conventional medicine) and asked why we still have them.

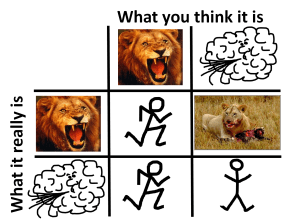

I think the diagram above was stolen from concepts that Michael Shermer discussed in a TED talk. I used it to explain a very basic thought experiment in human psychology. Imagine that you are a primitive human, millions of years ago on the African savannah. You hear a rustle in the bushes which could either be caused by a lion or the wind. If you assume that it is a lion and are correct, you survive with a small expenditure of energy (running away). If you assume it is the wind and are correct then you survive with no cost as you do not need to run away. If you assume it is a lion and it is really the wind then you still survive and waste the small amount of energy used to run away. Finally, if you assume it is the wind and it is actually a lion then you end up as lion food. Looking at this decision over the long term, it becomes immediately apparent that you can avoid being eaten (bad news in evolutionary terms…) by always assuming the rustle in the bushes is a lion. This demonstrates two important points: (i) it pays to quickly form associations between phenomena in the environment, and (ii) false beliefs can be rules of thumb for understanding the world with incomplete information.

2. Superstition in pigeons

I have always found BF Skinner’s work in pigeons very interesting (especially Project Pigeon). He spent a lot of time training pigeons to carry out various tasks in order to obtain food. In the example I cited, he placed pigeons in a cage where pecking a white dot resulted in food appearing. The birds readily formed an association between the behaviour and the reward and pecked away happily. However, the next step that Skinner took was fascinating. He turned off the mechanism that rewarded pigeons for pecking and presented food regularly but with no reference to the bird’s behaviour, then he sat back and recorded what happened:

One bird was conditioned to turn counter-clockwise about the cage, making two or three turns between reinforcements. Another repeatedly thrust its head into one of the upper corners of the cage. A third developed a ‘tossing’ response, as if placing its head beneath an invisible bar and lifting it repeatedly. Two birds developed a pendulum motion of the head and body, in which the head was extended forward and swung from right to left with a sharp movement followed by a somewhat slower return. The body generally followed the movement and a few steps might be taken when it was extensive. Another bird was conditioned to make incomplete pecking or brushing movements directed toward but not touching the floor.

– Skinner (1948)

Skinner considered these behaviours to be superstitions: the birds behaved as though there was a causal relationship even though there was none.

3. Superstition in computers

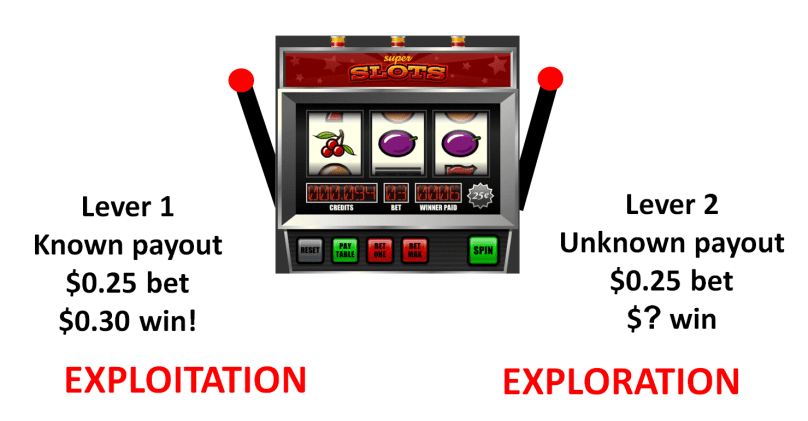

Animals are frequently used to study psychology because they are assumed to have less-complex cognitive machinery than humans. It logically follows, then, that we can also learn about psychology by stripping away all of the accumulated evolutionary adaptations to particular environments and simply analysing the reasoning machinery itself. Some mathematical modelling work done by my colleagues at Carleton University, Tom Sherratt and Kevin Abbott, did just this (Abbott and Sherratt, 2011). Kevin and Tom challenged computers to solve a problem called the “two-armed bandit problem“. Imagine a slot machine with two arms, as shown below.

If you pull the left lever you know that for a 25c bet you receive 30c in return. However, the machine has another arm and you have no information about how much that will pay you. Should you switch and “explore” the other arm or “exploit” the arm that you are familiar with? Kevin and Tom ran simulations on this problem and defined “superstition” as choosing the less profitable arm of the machine. They used Bayesian methods which allow the computer to possess a degree of belief prior to making a explore/exploit decision. They found a number of interesting results:

- Superstitions were more common when costs of the superstition are low relative to the perceived benefits. This is an intuitive finding. We frequently hear about people carrying around severed rabbits’ feet in an attempt to encourage good luck, but we seldom here of a “lucky ball-and-chain”…

- Superstitions were also more common when the prior belief was high. This means that, if you start off thinking that your lucky rabbit’s foot is going to help then it will take more exploration to dissuade you. If you are skeptical from the start then you aren’t likely to pick up superstitions.

- Finally, the more time you have to make a decision about which course of action to take, the more likely you are to not form superstitions. When you know that you have a long time to decide on a course of action, you can take the time to test the various options and work out which is actually the most beneficial.

4. Why we care about superstitions

This section gave me a chance to try to make the talk a little more grounded. The reason for the existence of groups like CFI, CASS and other skeptical groups is not only that we enjoy talking about science, but also because sometimes that science can benefit people or help avoid harm. I gave four examples of false beliefs or superstitions that were harmful: witchcraft in Africa, bomb-dowsing in Iraq, psychics in the USA and alternative medicine in the UK. You can follow the links to read more, but suffice it to say that considerable harm can be caused by false beliefs.

5. How do you solve a problem like superstition?

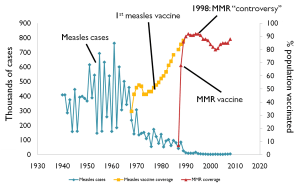

- Low costs – the previous section of my talk had pointed out that, while some superstitions involved relatively low costs, there were others that caused considerable harm. Here, I added that it was sometimes difficult for people to evaluate the costs involved with a superstition. For example, the costs of vaccination are negligible, but some people are obsessed with a non-existent link with autism. However, they are so focused on the possibly benefits of not vaccinating that they forget about the costs of not vaccinating. I highlighted statistics of measles cases that demonstrate the effectiveness of vaccines, a fact that many people have forgotten since those diseases were almost removed entirely. I highlighted the role of science in informing people of the costs and benefits of performing an action.

- Incomplete information – this is a clear example of where science can help. I raised the issue of alternative medicine and the abundance of research on topics such as prayer and homeopathy which have demonstrated that these kinds of interventions simply do not have an effect beyond placebo.

- Social learning – this was an issue that I had not previously considered. We get a lot of our information from those around us and have evolved to do so. This makes it very easy to be influenced by the opinions and thoughts of others. Thinking back to the lion on the savannah, it would be extremely useful to use the experiences of others to avoid lions, rather than needing to encounter one yourself before avoiding them. However, as Michael Shermer says “Thinking anecdotally comes naturally, thinking scientifically does not”. An over-reliance on anecdotes can cloud our judgement where cold, hard science would keep us safe.

- Placebo effect – I could have spent an hour talking about this… There is a push to attribute improvement in health or well-being to whatever intervention your recently too. However, the placebo effect means that you are likely to improve at least slightly just be expecting to do so.

- Failed logic – Related to this point are logical fallacies that we commit on a regular basis. These scupper our abilities to make rational judgements about relationships in the world. I gave two examples: (i) confirmation bias where we seek out corroborating information at the expense of dissenting information, and (ii) the “post hoc ergo propter hoc” (after this therefore because of this) fallacy, where we assume that because two things occur one after the other then there must be a causal link. In the case of the former, the answer is simply to seek that dissenting information out. Additionally, you have to be impartial to the results. I made the point that someone who had spent $60 on a Power Band might not want to look a fool, but they must be prepared to do so should the evidence point that way… For the PHEPH fallacy, the simple answer is to look for mechanisms. Why does it not rain when you wear your lucky socks? How are pieces of knitwear influencing meteorological phenomena?

- Superstitious people are not necessarily illogical, just under-informed

- Most superstitions are harmless, but some need to be resolved

- Science, as a way of thinking and a body of knowledge, helps avoid fallacies

- If you want to sink a Bismarck-class Battleship, use pigeons

____________________________________________________________

References

Abbott, K.R. & Sherratt T.N. (2011). The evolution of superstition through optimal use of incomplete information, Animal Behaviour, 82: 85-92.

Skinner, B.F. (1948) Superstition in the pigeon, Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38, 168-172.